It was an innocent meeting at a 2009 Cuban baseball reunion in Philadelphia. At the time, I didn’t know much about the Cuban Winter League, but I was very familiar with Minnie Miñoso. I decided to make the two hour drive from New York to interview the Cuban Comet and meet the others as well.

Sitting quietly at a table with not much fanfare was Cholly Naranjo. I did some scant research about his lone 1956 season with the Pittsburgh Pirates, but didn’t know the depths of his career. While the line was quite long for Miñoso, I decided to talk with Cholly. He was so vibrant and excited to share his memories. He told me he lived in South Florida and I should visit him the next time I go to see my mother, who also lived there.

Soon the wheels started turning. I found there was this corner of baseball I didn’t know; the Cuban Winter League's rich history. Cholly was the key. He knew everybody and had a story for seemingly everyone that played in the 1950s, as well as the decade before. He learned by watching his uncle Ramón Couto, who was a star catcher in Cuban winter league, Negro Leagues and minor leagues in the 1930s and 1940s.

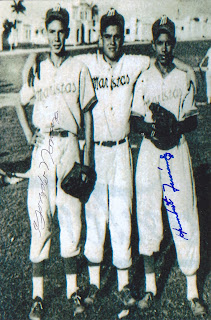

|

| Ramón Couto and Luis Tiant Sr. / Couto Family |

I leaned into Cholly for his encyclopedic knowledge. On almost a dime he could recall exact instances of players, games, and hilarious stories surrounding them. At the same time, he knew I was good with technology, so he would ask me to retrieve artifacts from his career. I later discovered just how much revisiting these stories kept him energized.

|

| Cholly (l.) in high school with Chico Fernandez (r.) |

We would talk weekly, sometimes about baseball, sometimes about life, relationships and everything else in between. As our trust increased, Cholly reached out to me to handle many of his other personal dealings, as he said I had the, “American style of communication.” Some reading this might think as a former major league baseball player, Cholly was swimming in financial riches; however, this was far from the truth. Due to Cholly being in the majors when baseball players needed four full seasons to earn a pension (now it is 43 days), he didn’t receive one. He figured out how to live his best life on a small social security check with help from some baseball organizations. I was often tasked with organizing the necessary correspondence to make sure everything was running smoothly.

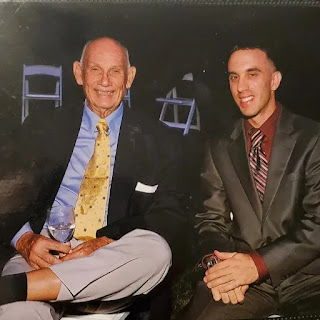

In 2010, he visited my home in New York for a few days. He was invited his cousin‘s wedding, who was Daniel Boggs' son, the Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. It was the first time Cholly visited New York since he returned from Cuba. We took the subway to the MLB offices to visit and personally thank the B.A.T. staff for their help. The trip to the MLB offices gave him so much validation behind his big league career.

|

| 2010 Wedding / N. Diunte |

The day before the wedding, he told me he wanted to go to the park to have a catch. I thought it was going to be a short session, but he just kept telling me to move back the longer we threw. Eventually, we were throwing from at least 120 feet apart. Mind you, Cholly was 77 at the time and he made the throws with ease! He finally said his arm was loose and as he shortened the distance, he showed me how to throw his famous curveball, the one Branch Rickey courted him for.

|

| Branch Rickey's 1956 Scouting Report |

After that trip to New York, I made it a point to visit 2-3 times per year. It was easy to visit my mother and then also spend a day or two with Cholly. I would meet him in Hialeah, and he would drive. It was on these winding card rides through Miami’s back streets where we bonded. He had story after story and told them with such clarity. He would take me to different Cuban restaurants, one’s that he thought I would enjoy. Every meal was “outstanding” in his words, and he was often right.

He had this little black book filled with telephone numbers. He would ask me who I wanted to see, and we would go. Every player he called said yes. They knew Cholly was genuine and took me in as the same. Everyone was relaxed, because as they all said, “it was family.” As I started to look around, I was slowly not only being accepted as part of that family, but his family as well.

|

| Cholly with Almendares |

Cholly’s major league stats don’t tell the whole story. It was deeper than that single season in Pittsburgh. He was a star pitcher in the Cuban Winter League from 1952 until 1961, primarily with Almendares. It’s hard to sit here and write down all the legends he encountered either as teammates or opponents. He loved discussing the 1954-55 Carribbean Series where his team had to face the Puerto Rican Santurce team with Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente in the same outfield (and the fight between Roger Bowman and Earl Rapp after Rapp misplayed a ball)!

He lit up talking about Jim Bunning who he faced in Cuba, who then later welcomed Cholly into his office in Washington D.C., or a young Brooks Robinson who played second base his one year in Cuba. Then there were Tommy Lasorda's hijinks after they won the championship in 1959. He told stories about Martin Dihigo, Satchel Paige, and his good friend Minnie Miñoso, who was also another tremendous gentleman.

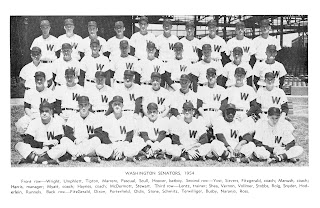

He almost made the majors in 1954 with the Washington Senators. He made it through all of spring training and they took him up north for Opening Day; Cholly even made the official team photo. A few hours before the first pitch, manager Bucky Harris informed Cholly they would be sending him to the minors on a 24-hour recall. He was disappointed, but he still stayed with the team for that day.

|

| 1954 Washington Senators |

President Eisenhower threw out the first pitch, and launched his throw into the crowd of ballplayers. Cholly ended up with the ball and had a historic catch with the President for a photo-op chronicled in Time magazine. The catch also earned him a spot on the TV show, “I’ve Got A Secret” the next morning.

He played with the Hollywood Stars in 1955 and 1956, when his team was the city’s main sports attraction (this was before the Dodgers and Giants moved). Famous entertainers would come to watch them play. Cholly regaled me with stories of his dinners and even dates with these luminaries. I wish I could remember them all, but the names have evaded my memory too.

He finally made the majors in 1956, coming up from Hollywood with his roommate and future Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski. Cholly saved his best performance for his final game, pitching 8 2/3 innings in relief for his first and only MLB victory. He told me how that win also kept Robin Roberts (whom he faced that day) from winning his 20th game of the season.

|

| Cholly Naranjo with Roberto Clemente 1956 Pirates |

Paul Casanova called me one afternoon in 2017, as MLB wanted to honor the Cuban players at the All-Star Game in Miami. He asked me to work as a liason for a group of players to help with the paperwork, negotiations and logistics. Cholly was one of the players in the group selected to be a part of the festivities, and without hesitation, he took me along for the ride.

|

| Cholly (r.) with Dr. Adrian Burgos (l.), Jose Tartabull (center) 2017 All-Star FanFest / N. Diunte |

For three days, Cholly was in heaven. MLB rolled out first class treatment, as did his peers. On the day he appeared at the FanFest to sign autographs and speak on a panel, MLB gave us a private SUV ride back and forth from the hotel to the convention center. They provided us both (yes me!) a private security detail that followed us through the FanFest. He was so excited to interact with the fans, as well as tell his stories on stage with José Tartabull and Dr. Adrian Burgos.

We spent the extended weekend with Luis Tiant, Tony Oliva, Bert Campaneris and Orlando Cepeda. It didn’t matter that Cholly wasn’t an All-Star or a Hall of Famer; not only was he readily accepted into the group, I found out they all looked up to him, as he was the senior member. Cepeda remarked how tough his curveball was on the rookie in winter ball. Tiant said he was a veteran influence on him as a rookie in the Cuban Winter League, and Oliva went out of his way to talk to B.A.T. to make sure Cholly was taken care of.

|

| Tony Oliva, Cholly Naranjo, Juan Marichal / N. Diunte |

We stayed up each night until 2AM talking about the game. The brotherhood was evident. Not only were they all there in the majors, they all faced the same challenges playing through the segregation in the United States. Every night, Cholly insisted at 84, to drive us back to my apartment in Fort Lauderdale. I was amazed how easily he navigated driving that late at night.

Things slowly started to change for Cholly after that wonderful weekend, and unfortunately, not in a good way. Paul Casanova died shortly after the Fan Fest (it was his last public appearance). Cholly worked with Casanova at the batting facility at Casanova’s home. He no longer had a place to go and interact. The young baseball players kept Cholly alive and the money Casanova paid him kept a little something extra in his pocket to enjoy life.

|

| Paul Casanova, myself, Cholly / N. Diunte |

Around 2019, Cholly stopped driving. He got into three accidents in a year and as he said, it was God’s way of letting him know he needed to get away from the wheel. I started noticing Cholly's once sharp mind started to show some cracks. He would lose his phone, or start to miss details in our conversations. Despite those missteps, when we sat down for a formal interview in 2019, he was amazed at how good he felt.

I saw Cholly early in 2020, right before the pandemic. We met for dinner, and he told me he walked for over 18 hours in a day just to prove to himself he could do it. I was amazed, but also feared for his safety, as the area in Miami where he lived wasn’t a walking city.

|

| Our last meeting July 2021 / N. Diunte |

Last year, he moved in with his nephew to be closer to the little family he had. I visited him in July 2021, as the pandemic put a huge wedge in my ability to travel. I could see the early stages of dementia from the time we spent together. A few months ago, Cholly had to be put into a nursing home, as he just couldn’t take care of himself any longer. Physically, he was in good shape, but he needed the care that comes with a nursing facility.

We would still talk on the phone a few times a week. When I called, it was always, “Coño! Nick! I am better than expected!” even as he struggled with recall. We kept the conversations short, but he always asked when I was coming down. I was aiming for the Christmas holiday to visit for a few days, but I came down with COVID on Christmas Eve. By the time I found a possible window to travel, his family let me know he also contracted COVID and wasn’t doing well in the hospital. I thought Cholly would miraculously find a way to pull through, but when the big man comes to get you off the mound, as Cholly would say, “You have to give up the ball.”

I am going to miss my friend. Cholly said he looked at me as a son, as he never had any children. I feel honored I was able to be a part of his life for so long and learn so much about his history, his culture and life story. I hope I can continue to elevate Cholly’s memory, as it was much greater than those 17 games he pitched with Pittsburgh in 1956.

QDEP Lazaro Ramón Gonzalo Naranjo Couto - November 25, 1933 - January 13, 2022.

Books Featuring Cholly Naranjo -

Last Seasons in Havana by Cesar Brioso

Growing Up Baseball by Harvey Frommer

Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History by Jorge Figueredo