.jpg) |

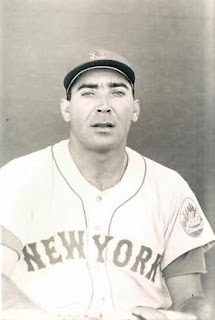

Ted Schreiber experienced every Brooklyn boy’s dream, making it to the major leagues with the New York Mets in 1963 after playing at James Madison High School and St. John’s University. While Schreiber’s MLB career lasted only one season, he represented a rich lineage of ballplayers who cut their teeth at the Parade Grounds on the way to the pros. Sadly, Schreiber died September 8, 2022, at his Boynton Beach, Florida home. He was 84.

Born July 11, 1938, Schreiber grew up a Brooklyn Dodgers fan, admiring legends like Duke Snider who would ironically become his teammate on the Mets. Schreiber first cut his teeth playing softball, only picking up baseball at age 15 when he attended high school.

At Madison, Schreiber was a multi-sport star, garnering St. John’s attention in both baseball and basketball, the latter in which he earned All-City honors. At St. John's, Schreiber continued playing both basketball and baseball. With the help of Jack Kaiser’s connections, he signed with the Boston Red Sox in 1959 for a $50,000 bonus spread out over four years. While in the Red Sox’s minor league system, he played with fellow New Yorkers Carl Yastrzemski and his Manhattan College rival Chuck Schilling. Schreiber quickly realized Schilling was blocking his path to the show and rejoiced when the Mets selected him in the Rule V draft at the end of the 1962 season.

As a second baseman, Schreiber faced intense competition on an otherwise hapless Mets team. He told author Rory Costello how Charlie Neal made sure the Brooklyn kid was on the field enough to gain manager Casey Stengel’s favor.

“I never had a rabbi with the Mets,” Schreiber said. “Larry Burright had Lavagetto. Ron Hunt had Solly Hemus, though I’ve got to say, he was a really good ballplayer. Another thing against me was that the Daily News and Journal-American were on strike that spring. They might have backed the local boy. If it wasn’t for Charlie Neal giving me some time in spring training, I wouldn’t have had a chance.”

Schreiber made the team out of spring training, but sparingly saw the field. After appearing in only six games, the Mets sent him down to the minor leagues where he could get more playing time. The Mets recalled him in July and remained with the club in a reserve role for the remainder of the season.

On September 18, 1963, Schreiber made history when he played in the final MLB game at the Polo Grounds. The Mets squared off against the Pirates in front of a sparce 1,752 spectators. Pinch hitting in the 9th inning, Schreiber hit a ball he was sure would evade Cookie Rojas’ glove. Rojas turned it into a double play that was the final two outs at the famed stadium.

“Sure, I remember the game because I made the last two outs,” Schreiber told me in 2011. “I thought I had a hit because I hit it up the middle, but Cookie Rojas made a great play on it. … That’s why I’m in the Hall of Fame; they put the ball there because the stadium was closed after that.”

Schreiber tried to hang on in the Mets farm system, but he chose to follow a teaching career which limited his availability to the summers. After doing double duty at Triple-A in 1964 and 1965, Schreiber decided to trade his cleats for chalk as a New York City teacher.

Perhaps Schreiber’s most significant legacy didn't come in a Mets uniform, but was the 27 years he spent as a math and physical education teacher at Charles Dewey Middle School in Sunset Park. He lived in Staten Island until his retirement, moving to Centerville, Georgia, and then settling in Boynton Beach until his passing.

*ed note - Rory Costello has been attributed to the Charlie Neal story.