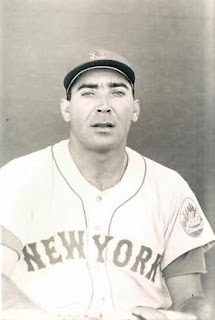

Rogelio "Borrego" Alvarez, former first baseman for the Cincinnati Reds and Cuban Winter League star, died Friday evening in Hialeah, Florida due to complications from

kidney failure according to a former teammate who wished to remain

anonymous. He was 74.

|

| Rogelio Alvarez |

Alvarez was signed by the Cincinnati Reds in 1956 out of his hometown of Pinar del Rio, Cuba. I interviewed Alvarez at his home in February 2011, and he vividly recalled his tough transition from Cuba to the United States.

“I was 17 and a half,” Alvarez said. “That year, we came about eight of us all together to Douglass, Georgia. It was a little town, and we went there to train.

“I didn’t know it was so bad, the colored people couldn’t go no place. The white people stayed in the good hotel, we had to go to the black community and stay in a house, stuff like that. We didn’t understand the bad words, so we didn’t know what they said.”

Even worse for Alvarez, he didn’t speak English, and was quickly separated from his Cuban counterparts. The social isolation weighed heavily on the new arrival.

“We had two blacks, me and Leo Cardenas,” he said. “They had 14 teams and they didn’t want colored people. Cardenas got signed and went to Tucson in the Arizona Mexican League. They [Tucson] said, ‘We like you too, but we have a first baseman.’ They left me in Georgia. That broke my heart, to see everybody going and I’m going to stay by myself with no English. Nobody else spoke Spanish.”

Approximately a month later, Alvarez was assigned to the Reds’ affiliate in Port Arthur, Texas. It was another wild journey for the young Cuban on his ascent to the major leagues.

“After a month being on my own there, they called me one day and send someone with a letter, they wanted me to go to Port Arthur,” he said. “They took me to the bus station. I went to Atlanta and changed planes without speaking in the airport. They told me, ‘Everywhere you go, you show this letter.’ If I lose this letter, I can’t find nobody. The letter said, ‘This man is a ballplayer for Cincinnati, and doesn’t speak English. He’s going to Port Arthur; please help him out, Cincinnati will pay any charges.’”

As soon as he arrived, the face of Jim Crow loomed large. Armed with only the letter from the Reds, he watched yellow cabs pass him by until finally a black cab stopped to take him to his destination.

“When I got to Port Arthur, there were two cabs, a yellow cab and another cab,” he recalled. “I wanted a yellow and they said no, you take the black cab. I showed them the letter, and they took me to the little town in Port Arthur, the black community.

"The old lady there, she didn’t say nothing. They got a Cuban guy, I didn’t know how they found him, but he came. He talked to me and he told the lady who I am and showed her the schedule that I go week in and week out, and I needed the room. I go downstairs to the kitchen and eat. I sit down and they come with a menu. I can’t read it or talk. She asked what I want, grabbed my hand, and went to the kitchen. They opened the pot; they [pointed to each] and said, ‘Stewed beef, rice, red beans, and cornbread.’ I ate that meal for a whole month.”

Alvarez’s first day at the park was no picnic either, as he found himself isolated in more ways than one. Even in the locker room, the club found a way to segregate Alvarez from his teammates.

“When I came to the ballpark the first day, I was the only black of 16 ballplayers,” he said. “There was no seat for me. I had to change in the bathroom. The bathroom was my locker. The manager threw me a uniform and it didn’t fit me right. I only weighed 185 lbs.”

Eventually with the help of a local young girl, Alvarez was able to pick up the language and adjust to life in the United States. Over fifty years later, he still was taken back by how quickly he took to speaking English.

“A little girl asked me to see a movie and in three months, I learned what I know,” he said. “I learned fast; it was unbelievable. They were surprised how fast I learned.”

Despite all of the off-the-field adjustments he had to make, he batted over .300 for Port Arthur. Alvarez returned to Cuba in the off-season, but struggled to get on with one of the four main clubs.

“It took me three years to get on with a team in Cuba,” he said. “My first year, I was a reserve with Cienfuegos. They were people ahead of me, Frank Herrera and Chiquitin Cabrera. I had to go to Nicaragua in the winter because I didn’t play regularly in Cuba.”

Fortunately for Alvarez leaving Cuba to play winter ball proved invaluable to sharpen his skills. Playing in Nicaragua provided him with an opportunity that was far greater than any home run he could hit; he met his future wife there too.

“That’s where I met my wife in 1957,” he said. “I had a good year there. I was second in home runs in the league and after that year, I went back to the Sugar Kings. Then I went back to the reserve and played a little bit more. In the winter of 1959, I played regularly.”

His play in the winter of 1959 when he batted .333 with two home runs in the Caribbean Series, contributed to the mighty success of the Cienfuegos team. They swept the Caribbean Series in six games.

“We won the Caribbean Series and we won six out of six," he said. “We had Pedro Ramos, Camilo Pascual, Joe Azcue, Ossie Alvarez, Leo Cardenas, Chico Ruiz, Roman Mejias, Ultus Alvarez, Cookie Rojas, and I. We beat everyone in Cuba.”

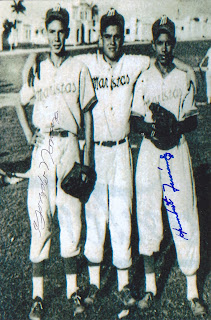

|

| Rogelio Alvarez (r.) with George Altman (l.) and Pedro Ramos (c.) with Cienfuegos / Author's Collection |

Nineteen-sixty marked a period of turmoil during the Cuban revolution, one that Alvarez found himself dangerously close to. While playing with the Havana Sugar Kings, shots broke out during a game against the Rochester Red Wings.

“It happened in Cuba stadium,” he said. “That was the last game we played there. We played against Rochester. Frank Verdi was on third base. There were at least 20 police in the stadium watching. You heard, ‘Clack! Clack!’ and one of the bullets came down and hit Frank Verdi. They said we don’t play no more, so we had to move. We found Jersey City.”

Rounding out the rest of the year in New Jersey, Alvarez was all packed and ready to go to Cuba when his plans were suddenly altered. His call to the show finally arrived.

“Orlando Pena and I were playing for Havana / Jersey City,” he said. “We ended the season in Columbus. Right after the game, we didn’t know that we were going to go; I packed my stuff, ready to go to Cuba to see my people.”

He went one-for-nine during his September call-up with the Reds. The adjustment to the pitching during his first stay in the major was tough.

“I wasn’t ready when that happened,” he said. “I didn’t see that many good pitchers [in the minors]. You went up there and they had four good starters. You’ve gotta be ready, and I wasn’t ready.”

He played one more season for Jersey City and then was sold to the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League in 1962. After having a banner year, batting .318 with 18 home runs, the Reds called once again.

“We won the pennant [in San Diego], that’s why they didn’t bring me up before, because we were fighting for the pennant,” he said. “The manager was crazy for me. He gave me the Most Valuable Player. The manager Don Heffner, after we won the pennant, we came back to San Diego. He called me to the office to come see him. He said, ‘Here, take a beer with me. You’re going to Cincinnati tomorrow.’”

Fresh off of his best minor league season, Alvarez's confidence skyrocketed. This time, he had no questions about his readiness for the majors.

“Oh my goodness! I wanted to go to Cincinnati,” he said. “They waited for me in the airport. They took me right to the stadium, dressed and I went to play. I didn’t play because it was a right handed pitcher. I didn’t do too good, but I was ready then.”

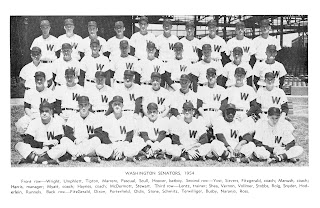

He was sold to the Washington Senators after the 1962 season, but the deal was complicated by his return to Cuba. Ignoring the advice of many, a stubborn Alvarez went home despite the many restrictions on travel to and from Cuba.

“After the season I went to Cuba, I didn’t listen to nobody,” he said. “My idea was made and I went. That was a mistake. They sold me to Washington. I didn’t know they were going to send me.”

According to an Associated Press report in 1963, Alvarez could not get permission to leave Cuba to report to the Senators. While San Diego general manager Eddie Leishman refused to comment on how Alvarez finally arrived there, Alvarez, almost 50 years later filled in the details.

“I went through Mexico to get back to San Diego,” Alvarez revealed.

The story of Alvarez’s return to San Diego in 1963 after missing all of spring training and almost the first two months of the season, is one that everyone who has ever played baseball has wished they could have lived to tell.

“That day I can never forget. I get there, and they came back that night. In the morning, I went to practice. The owner said, ‘I’m going to try some kids. You get some balls, hit, and run, and then in the afternoon you come back with the big team.’ I practice, took a shower, and drank a couple of beers. I figured they would give me a week to practice,” he said.

His manager Don Heffner, however, had different plans. As long as Alvarez was in uniform, no matter how rusty he was, Heffner wanted him available on the bench.

“The manager Heffner said. ‘Hey where are you going?’ I said, ‘I’m going to sit in the stands.’ He said, ‘No, come put your uniform and come to the dugout.’ I said, ‘I’m not in shape.’ He said, ‘I want to see you in the dugout.’ I didn’t go to the dugout, I stayed in the bullpen. All game, I was with the pitchers, talking with Jim Maloney,” he said.

Alvarez, who figured that he wouldn't be put in the game after such a long layoff, was lounging the in the bullpen the entire game. He was totally unprepared for what happened next.

“In the 9th inning, the bases are loaded, and Tommy Helms comes to hit,” he said. “The manager calls timeout [and] points to the bullpen. The pitchers said, ‘Heffner called you.’ The game was tied. I said, ‘Me, nah, that’s for you.’ They said, ‘That’s gotta be you.’ I face him [Heffner] and said, ‘Me?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’

"When I go, people start clapping. Everybody stands up and all of the people go crazy. The pitcher was Lew Krausse; he had good stuff. The first pitch, what I saw was woosh! They called a strike! I didn’t see it. He threw hard. After that, he threw me a curveball. Crazy! As a right handed hitter, I didn’t play ball for six months, keep it fast! He threw a breaking pitch; he gave me a chance to see [it]. When I saw the pitch, it stopped, and it stopped breaking. I go with it, and it was a home run! First swing, home run with the bases loaded. Oh my goodness! I was like a king. It was in the papers, headlines, ‘Fat Borrego wins the game with a home run for the Padres!'”

Alvarez played through 1967 in the Reds system, swatting 226 home runs in 12 minor league seasons. He then played an additional six years in the Mexican League before ending his career in 1973. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame of the Cuban Baseball Players in Exile in 1998. Alvarez was also honored earlier this year in February at a ceremony for the Cuban Sports Hall of Fame at the Big Five Club in Miami.