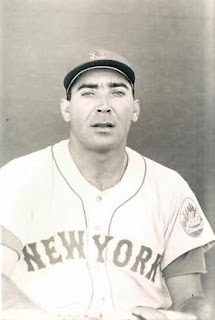

Hector Maestri, one of only nine major leaguers to ever play for both versions of the Washington Senators,

passed away Friday February 21, 2014 in Miami according to his former teammate Jose Padilla. He was 78.

Born April 19, 1935 in La Habana, Cuba,

Maestri was originally signed as a shortstop to the Senators

organization in 1956 by the legendary scout Joe Cambria. Excited with

the opportunity to follow in the Senators pipeline of rich Cuban talent,

Maestri’s world was turned upside down only a few weeks into his

professional baseball career.

“I played three [sic] games in Fort Walton Beach and they released me,” said Maestri in a 2012 interview with the author.

|

| Hector Maestri Card / N. Diunte |

Even though Maestri was deeply disappointed by the lack of a time the

Senators gave him, he did not want to return to Cuba. Instead, he went

to Houston to live with his uncle and work. It was there that he had a

second chance at his baseball career.

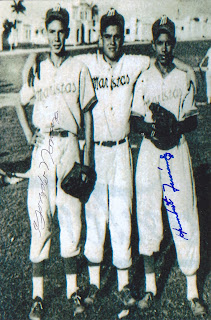

“My uncle introduced me to a Mexican-American who had a baseball team

out there,” he said. “The guy wanted me to play with him, so they gave

me a job and I played baseball.”

While he was playing on the semi-pro circuit in Houston, he was

approached by Senators scout Joe Pastor who offered him another shot

with Washington. Maestri had his reservations about re-signing with the

organization.

“I told him I was very angry because they didn’t give me a chance,” he said. “Fifteen days wasn’t enough.”

After Pastor reassured him that he would get a longer look, Cambria

signed Maestri during the off-season in Cuba. Blessed with an

exceptional arm, Maestri still fancied himself as a shortstop, but the

Senators had other plans. Maestri split time between pitching and the

infield in 1957 with Class D Elmira, N.Y., but when he was asked to

pitch an impromptu bullpen session for Senators Vice President Joe

Haynes during spring training in 1958, management made it very clear

what his permanent role would be.

“The bullpen was near the clubhouse,” he recalled. “Anytime you threw

the ball, there was a big echo. When I threw the ball, I looked [over]

at him and he was smiling.

“The people in the clubhouse came out and said, ‘Dammit, who was

throwing that ball?’ I was throwing very, very hard. We didn’t have

radar guns, but they told me I was around 95. Mr. Joe Haynes came to me

and said, ‘If I see you in the infield, I will throw you out. You are a

pitcher.’”

Maestri spent another season at Elmira honing his craft on the mound,

and it paid off. He finished with a 16-11 record, broke the league

record for strikeouts and earned MVP honors for the team.

“I broke the strikeout record of Sal Maglie,” Maestri said. “He had 198 and I put [up] 210 in 156 innings.”

In 1959, he inched his way closer to the majors, playing at Class B

Fox Cities where he was pared up with player-manager Jack McKeon. His

11-7 record earned him a AAA contract with Washington’s affiliate in

Charleston.

He went home that winter and pitched for Cienfuegos in the Cuban

Winter League, leading them to not only the league championships, but a

sweep of the 1960 Caribbean Series.

It was the beginning of a year filled with highlights for the

hard-throwing Cuban pitcher; however, it wasn't a straight rise to the

top. Coming off of his championships in winter ball, he hit a bump in

the road at the end of spring training in 1960. Just as the season was

about to start, Charleston sent him down to Charlotte in the Class A

Sally League. He wasn’t pleased with the decision and set out to prove

to management that they made a mistake demoting him.

“I go to Charlotte, and on the first day our manager Gene Verble, told me I was going to be in short relief,” he recalled.

Verble summoned Maestri to close the game, and he delivered the goods.

“I threw nine pitches and struck out all three guys,” he said.

Nineteen-sixty was a banner year for Maestri. He was cited in the

August 28, 1960 issue of Sports Illustrated for pitching a perfect game in relief during the course of the season.

“Hector Maestri, Charlotte (N.C.) South Atlantic League relief

pitcher, did not give up a walk, a hit or a run in hurling nine

consecutive innings of perfect baseball over a five-game span, went 16

consecutive innings before yielding his first hit.”

Cut from the organization only a few years earlier, Maestri made good

on his second calling, earning a promotion to the major league club

when rosters expanded in September. Biding his time in the bullpen, he

finally was put into action on September 24, 1960 in relief against the

Baltimore Orioles.

“I pitched two innings and didn’t allow any runs,” he said.

Maestri carried that momentum into winter ball, winning another

championship with Cienfuegos. Along with his second championship came

another career altering event, the 1961 Expansion Draft.

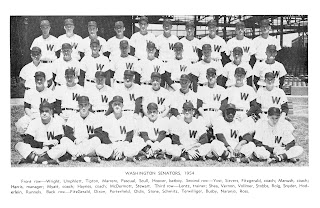

The original Washington Senators became the Minnesota Twins and

Washington created a new team to represent the nation’s capital.

The new Senators paid Clark Griffith $75,000 for the rights to Maestri. He saw this as an opportunity to negotiate for a higher salary.

“At that time the big league contract was $6,000,” he said. “I was so

fresh, I said, ‘If you don’t give me $15,000, I don’t go.’”

To further complicate matters,

relations between Fidel Castro and the United States went sour,

leaving the future of all of the Cuban players, including Maestri in

doubt. Luckily for Maestri, tensions eased up and he was able to

negotiate a raise to $11,000.

Unfortunately, all of his negotiations didn’t account to much because

Maestri couldn’t curry enough favor with manager Mickey Vernon to make

his way up north with the team to start the season. Vernon thought

Maestri needed more seasoning and sent him back to the minors for most

of 1961.

Once again, determined to show he belonged, he burned up the Sally

League with a 10-1 record for Columbia. This impressive performance

forced the Senators and manager Vernon to take another look at the Cuban

fireballer.

“I was a relief pitcher all my baseball career,” he said. “Mickey

Vernon came to me and said, ‘You are pitching tomorrow, starting against

Kansas City.”

Not used to starting, Maestri soldiered on anyways. He took the ball and went six strong innings against the Athletics.

“I lost 2-1 and that was it,” he said.

He wouldn’t get back to the major leagues for the remainder of his

baseball career, and almost didn’t get back to the United States. After

the 1962 season, he returned to Cuba to see his newborn son. At the

time, Castro wasn’t letting anymore players freely leave the country.

“When I got in Cuba, they didn’t let me get out," he said. "That ruined my career.”

Maestri was done at 27, or so he thought. A call from a Mexican League team gave him a new lease on his baseball career.

“I had taken a few years off when I got a call from the Mexican

League to play ball,” Maestri said. “Veracruz called me. They asked what

I wanted. I told them I wanted a visa for my wife and my two sons. They

told me, no problem. That’s how I got out of Cuba, [through] Mexico, in

1965.

“When I finished the league in Mexico, I went to the United States

embassy in Veracruz and I asked for asylum. They didn’t give it to me,

but they gave me a chance to talk to a wonderful guy, Phil Howser. (The

general manager of the Charlotte minor league team.) I told him that I

didn’t want to go back to Cuba anymore. He said, ‘Stay right there in

the embassy, let me talk to the ambassador.’ I didn’t know what he was

talking about. The guy came to me and told me to go back to my apartment

and come back tomorrow morning. I got my visa and jumped.”

Charlotte signed him for the 1965 season. He played one more year in

the United States for the Wilson Tobs in 1966. Citing the lack of pay

and burdensome travel schedule, he moved on from professional baseball.

“If you have a family, you have to do something because you can’t

travel with your family,” he said. “My two sons had to go to school, so I

said to my wife let’s go. I bought a car up there and came to Miami.”

Maestri had his own business career in Miami and his wife worked for

the telephone company. Both of his sons grew up to be engineers,

something he was very proud of.

“I owned my house and my kids got their education," he said. "It was wonderful.”